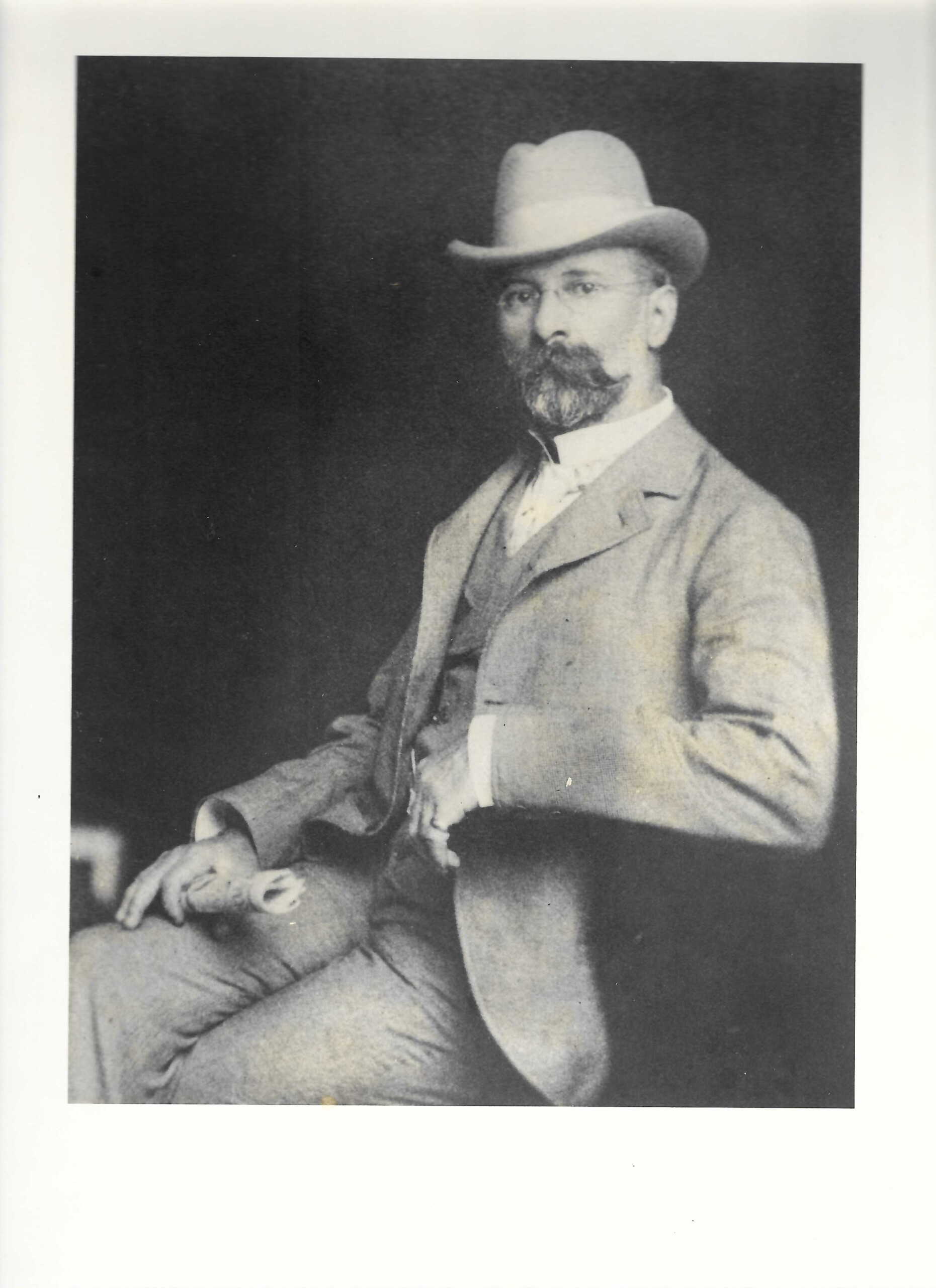

The summer of 1904 might have been the nadir of Simon W. Wardwell Jr.’s adult life. At age 54, he felt worn out, mentally and physically. He daily worked 18 hours trying to improve textile machines he had invented for the Universal Winding Company, and casting about for new inventions that he could bring to market. In the few hours he spent in bed, he obsessively wrote poetry while sitting up; he continued to “skribble” poetry while sipping coffee at breakfast, his mind unable to just idle.

That September, Wardwell struck up a conversation about braiding machines with a 38-year-old foreman in one of his factories, Edward H. Parks. Parks and Wardwell began an examination of braiding machines made at places such as New England Butt in Providence, and they found them woefully inefficient. They set about improving the machine, and within two months crafted a small, prototype that braided candlewicks.

In April 1905, Wardwell and Parks obtained patents for an entirely new type of braiding machine. The genius of their machine was their method of raising and lowering taut strands unwinding from spools and bobbins rotating in opposite directions around a central braiding point. This method of revolving fixed spools and bobbins in opposite directions while raising and lowering their unwinding strands created a tighter, more consistent braid than conventional braiding machines could produce. The Wardwell-Parks braider dramatically improved braiding for cable used to transmit electronic signals. The new machine’s tighter, more consistent weave reduced the “structural return loss” of a signal, vastly improving efficiency for all sorts of uses, and the machine is still manufactured today for braiding cable in cellphones, computers and keyboards, shoelaces, ironing cords, medical stitches.

For Wardwell, obtaining novel patents was nothing new. He received his first patent in 1871, at age 22, for a rotating sewing machine table. He received his last patent posthumously, for a braiding machine improvement, more than 50 years later. In between, he earned more than 150 US patents, few of them with any lasting value. Only two categories of his patents proved truly profitable: those for the Universal Winding Machine, which efficiently wound thread and yarn onto textile machines throughout the world; and those, that he shared with Parks, for the Wardwell Braiding Machine.

Wardwell hailed from a family of 13 children, raised in the Appalachian Mountains of western Maryland, where their father, Simon, was an agent obtaining timber for a Baltimore lumber company. The mother, Matilda, died shortly after the birth of her 13th child, and Simon Jr.’s formal education ceased about that time, when he was only 9.

Wardwell’s older brother, Ernest, a Civil War Soldier stationed in New Bern, N.C., took custody of him in New Bern near the close of the Civil War. In his early teens, the younger Wardwell struck out for the West, alighting in St. Louis, where a group of investors backed the prodigy’s invention of a lock stitch sewing machine by forming the Wardwell Manufacturing Company. The company surrendered its assets after only five years, but the experience launched young Wardwell on a career of inventing many kinds of things, the most successful of which were machines for the textile industry.

After Wardwell Manufacturing failed in 1879, Wardwell moved to Woonsocket, RI to work for the Hautin Sewing Machine Company. While he tinkered with sewing machines, Wardwell also drafted plans for methods of more efficiently winding thread onto spools and bobbins. To fund development of his ideas for a winding machine, Wardwell turned to Joseph Leeson of Boston. In 1893, Wardwell agreed to sell Leeson all of his future patents for $1,000 and a large share of the new Universal Winding Company’s stock. That partnership proved profitable, but it ended acrimoniously in 1910, when Wardwell sold his stock back to the company and used the capital to help incorporate the Wardwell Braiding Machine Company.

Wardwell ran the Braiding Machine Company for 10 years, before his death in 1921 at the private, Keith Hospital in Providence. In his will, Wardwell put control of Wardwell Braiding in the hands of trustees, and left pro-rata shares of annual income from the company to his four sisters; his brother, Ernest; the trustees and their successors, and any employee trustees deemed “loyal” to him. As each sister and brother died, their daughters, Wardwell’s nieces, would receive that share of the money. As each niece died, her daughters received the share. Upon the death of his last grand-niece, the trustees were to dispose of the entire trust, granting it to causes that Wardwell favored such as building model hospitals, kindergartens, housing for elderly couples, and vocational education. The last of his grand-nieces died in 2020, and the trustees of the Simon W. Wardwell Foundation continue seeking applicants for Foundation funding.